(Romans 8:28, translated by William Barclay)

I think of it as my time in the laboratory; those days and nights that I serve as a chaplain in a hospital. It is there within the domain of growing malignancies, transplants, code blues, interminable waiting, and death that I have opportunity to field test the doctrines of God’s love that I preach and teach.

Recently after leading a worship service in the hospital’s chapel, three worshippers stayed to talk. We pulled up chairs, sat and listened as each told their story. The first was a young, slick headed cancer patient tethered to his intravenous tubing as it pumped chemicals into his withering body. Then there was the mother of a special needs adult patient who was battling drug resistant bacteria after his kidney transplant. Her husband and daughter had recently been killed in an automobile accident on their way to visit the patient.

Our third worshipper was the wife of a patient with a long history of heart disease who had just been diagnosed with cancer, and his prognosis uncertain. As she talked, she gathered up pain from her past and told of their teenage son who had died from a brain tumor. In these moments of tears, sufferings, and wrestling, I talk with God and pour out my questions to Him. I often wonder about His plan and purpose for us all.

I once sat outside my young wife’s hospital room as she was dying from cancer and listened as a well-intentioned visitor reminded me that “God works all things together for good.” I realized then how trite and even cruel such words can sound to someone in agony and mind numbing confusion. Christian lingo can often be hurtful to the hurting. And yet, in my calmer, more collected moments, I do believe that God works all things together for good. I am convinced of his power to redeem the irredeemable. While I haven’t always believed this in the pain of the moment, it is something I try to hold on to. But it was a novelist who helped me gain a richer understanding of God’s promise to us to bring good out of bad.

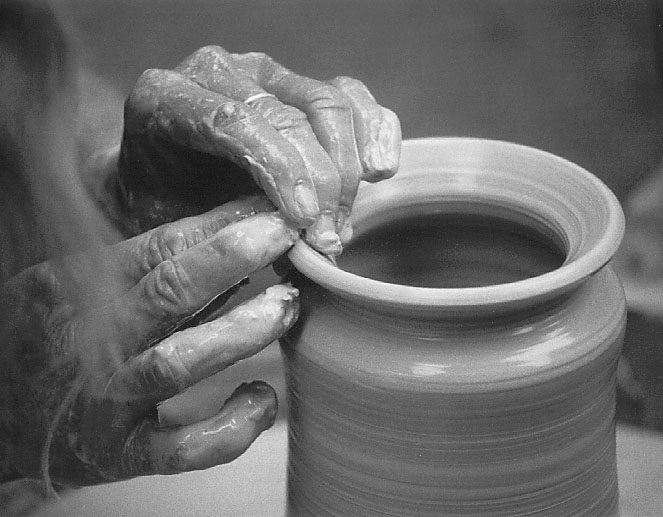

I think it was Providence that led me years ago to pick up the novel Absolute Truths, by Susan Howatch. I had not heard of the author, or the book, but from the first page onward I was enthralled. Howatch weaves a story about The Rev. Dr. Charles Ashworth, a Cambridge academic whose life falls apart after the death of his wife. Then one day as he is passing through a spiritual and nervous breakdown, he happens to visit a sculptor. In the sculptor’s studio is her latest work, an exquisite and moving pair of hands.

As The Rev. Dr. Ashworth marvels at the creation in clay, he is led into a discussion with the sculptor about the creative process and her work. The sculptor says to Ashworth:

“Every step I take, every bit of clay I ever touch, they are all there inthe final work. If they hadn’t happened, then this (pointing to the sculpture) wouldn’t exist. In fact they had to happen for the work to emerge as it is. So in the end every major disaster, every tiny error, every wrong turning, every fragment of discarded clay, all the blood, sweat and tears, everything has meaning. I give it meaning. I re-use, re-shape, re-cast all that goes wrong so that, in the end, nothing is wasted and nothing is without significance and nothing ceases to be precious to me”.

As Ashworth’s story unfolds, he begins to see his own life as the clay in the hands of a skilled sculptor. He begins to believe that God is taking all his pain and wrong turnings and reworking them within his life to create a new life. As I read about The Rev. Dr. Ashworth, I dared to believe that the Divine Sculptor was also working in my life to make something new.

It is later in the novel that a fellow priest, Jon Darrow, reminds Ashworth of the real meaning of Romans 8:28. Darrow points out that “The correct translation of the passage is actually: ‘All things intermingle for good to them that love God.” Ashworth remembers the verb under discussion and knows that Darrow is right to render it as “intermingle.” The Cambridge scholar knows that is one of the meanings of the word.

Then Darrow continues his discourse on Romans 8:28 by adding: “The light and the dark intermingle to form the pattern of redemption and salvation. The dark doesn’t become less terrible but that pattern which the light makes upon it contains the meaning which will redeem the suffering.”

The pattern that will redeem the suffering! That becomes the theme of Absoute Truths, that whatever happens to us, whether good or bad, can be redeemed in the hands of our creative and powerful God. As the sculptor does with the clay, so God knows how to take and shape and refashion our lives even in the most hopeless situations.

As I was reading Absolute Truths, and thinking about God’s power to intermingle all things for good, I realized that this was more than the power of positive thinking, or some mind over matter mantra to numb us to life’s cruelties. There is something far deeper, more profound that is going on. Eventually Ashworth learned what I believe God is still teaching me: “only the final pattern of our completed lives would show the full breadth and depth of redemption, and now I had to settle for seeing mere fragments of light, through a glass darkly.”

The promise of God to intermingle all that happens to us for good flows into Apostle Paul’s stunning crescendo at the end of Romans 8. It is here that Paul expresses his unshakeable confidence in the purpose of God in our lives. Paul rhapsodizes how “if God is for us, what can be against us?” and “what can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus?” Paul testifies by the Spirit of God that nothing will ever be able to separate us from the love of God!

Often when death camp survivor Corrie ten Boom spoke to groups of people, she would hold up an old embroidered bookmark with frayed and tangled threads hanging from the back side. She would point out how the tangled threads on the back seemed purposeless and without design. Then Corrie would smile, turn over the bookmark, and point to the words embroidered on the front side: “God is Love.”

When I am a witness to people’s unspeakable pain, or pass through it myself, I think of God’s handiwork and the tangled threads of our existence, and cling to the unshakeable truth: “God is Love.” He intermingles the difficult and painful things for our good. I often like to go back to and ponder the simple but profound truth put to paper by the anonymous poet in “The Divine Weaver.”

Not till the loom is silent.

And the shuttles cease to fly

Shall God unroll the pattern

And explain the reason why

The dark threads are as needful

In the weaver’s skilful hand,

As the threads of gold and silver

In the pattern he had planned.

Grace and peace–Tim Smith

Photo by Toby Thain